The Teacher Who Really Saw It All

by etoribio • September 26, 2011 • News • 0 Comments

Homer Panteloglou was in the middle of teaching a class a block from the World Trade Center when the first plane hit on 9/11. PHOTO/Elyse Toribio

By ELYSE TORIBIO

NEW YORK – On the morning when the image of the burning building a mere .6 miles away was on the television screens of most people around the world, the students of the High School of Economics and Finances, or “Echo” as they liked to call it, had absolutely no idea what was going on.

The school’s architecture was unusual, and still is, even after everything came crumbling down around it. Only the top three floors have windows. Floor 8 serves as the school’s cafeteria (unoccupied so early in the day), while the 9th and 10th floor hold the offices of administrators.

Standing at 10 stories tall with a facade of gray brick, the building is in dire need of a good scrubbing. One almost gets the sense there’s still a thin coat of dust from the remnants of that horrifyingly beautiful morning 10 years ago.

It is the building where Homer Panteloglou, a marine biology teacher at Echo, has taught for 13 years. For Panteloglou, that morning started at 5 a.m. in Long Island, NY. After working for over a decade in Lower Manhattan, the hourlong commute had become routine. Only Sept. 11, 2001 was not an ordinary day.

“It was gorgeous,” Panteloglou said, eyes closed as he recalled the details of the morning. “Seventy degrees or something like that. Very dry, not too hot, not too cold…Perfect.”

If the day had gone any differently, if two 767s had not been barreling towards New York City as Panteloglou began his first class of the morning, the only detail he would have remembered from that day might have been the fact that he had run into an old friend on the train ride into the city.

Only Sept. 11, 2001 turned out to be anything but forgettable. What happened next for a school of approximately 800 students would become a lifelong lesson of living history, of survival, and of making sense of a tragedy no young adult should ever have experienced. A tragedy that left them displaced and feeling abandoned by the city that they loved.

“Lower Manhattan was in chaos”

The High School of Economics and Finance, once the home of New York University’s business school, is located on Trinity Place in the heart of the Manhattan’s financial district. This is no coincidence. Students are expected to abide by a strict professional dress code on Wednesdays, and most take part in internship programs at firms in the area. Standing a mere two blocks from the World Trade Center, the school had a primary focus on the world of economics. That morning, though, Panteloglou’s primary focus was teaching a science lesson to a classroom of groggy students.

Located on Trinity Place, the High School of Economics and Finance shook when the south tower of the World Trade Center was struck on Sept. 11, 2001. PHOTO BY ELYSE TORIBIO

“I didn’t even realize when the first plane hit the building,” Panteloglou said, “No child really saw what was going on. Now if you were teaching, which I was, then you saw nothing. All you did was hear commotion.”

A few minutes after the first plane hit the North Tower, a shelter drill was called at the high school. Students were kept in the classroom— with no windows, that was the safest place for them to be.

Panteloglou’s colleague across the hall didn’t have a class that period, and was able to go and find out what had caused the unscheduled drill.

He returned with strange news.

“Something flew into the Trade Center.” Assuming that one of the helicopters that did tours around the city had had some sort of freak accident, Panteloglou only replied, “Oh, that’s not good.” A terrorist attack was the furthest thing from his mind, until at that moment he felt the school shake as the second plane reached its destination at the South Tower.

At that point, “I knew something was up,” Panteloglou said. “The kids started to panic…I was trying to entertain them as much as possible and keep them calm.”

Though he tried to keep a brave face, Panteloglou was starting to realize that something was wrong.

“I could hear it in the secretary’s voice when she called the drill,” he said. “Her office…she probably saw what happened. They were probably freaking out up on the 10th floor.”

Homer Panteloglou and the rest of the faculty led the students outside once an evacuation was called soon after. And finally, they were able to see it all. Behind them, the buildings were ablaze and people were dashing around them in a panic.

“Coming out of the building, it was complete chaos,” Panteloglou said. “Lower Manhattan was in chaos.”

As he describes it, there were seas of people running south toward Battery Park. Walking out of school building, Panteloglou craned his neck up to see the buildings aflame. There was something else he was seeing too, though he didn’t realize it immediately.

“I saw people falli—” he faltered. “I didn’t realize it was people jumping, but yeah. I saw some of that too.”

With the mayhem that surrounded him, Panteloglou was separated from the group. He headed south, trying to gather as many students as he could on his way to Battery Park. Finally, he ran into a colleague that had rounded up about 25 students. A student there had lost her sister, and was moving back up to the high school to find her.

Panteloglou turned her away, insisting that he would go back and find the sibling.

“I was going against the crowd, so that wasn’t fun,” Panteloglou said. He passed masses of people, most who were running, some who were loitering and looting from abandoned stores, and others who were videotaping the scene, something Panteloglou still doesn’t understand.

Right about then, the south tower collapsed.

“I saw it go down,” Panteloglou said. “It was surreal. Absolutely surreal, I felt like I was living on film. Scary, actually. Lower Manhattan was…we were in sunlight, and then you look behind you and it was complete darkness,” Panteloglou said. “It was night.”

Forced to turn around, Panteloglou reunited with his colleague and some students, and began to head north on the FDR drive.

“It was like another world.”

Panteloglou trekked uptown with the students he and his colleague were able to gather. They were headed toward 89th and York avenue, where the colleague had an apartment.

At 13.4 miles long and 2.3 miles at its widest point, the island of Manhattan isn’t exactly what one would call the biggest city in the world, in terms of area. And with a population of over 8 million people, it’s easy to assume how fast news can travel. Strangely enough, the further north the group got, the more they realized how detached people were from what was going on.

“People knew what was going on, but they didn’t have the same concern or panic,” Panteloglou said. “They were watching it on television, but it was just like they were just watching it on television.”

There were some residents in the area who stood outside handing out water to those who were walking from downtown, covered in ash from head to toe. But others weren’t so sympathetic.

Panteloglou recalls that one of the students he was walking with got nauseous and threw up in front of the store. “The storeowner came out and was yelling at him. It was weird.”

Finally at their destination, Panteloglou and his colleagues tried to keep everyone’s mind off of what was going on. They bought a cupcake for a student who was celebrating a birthday, and tried not to watch television, ignoring the rumors that were floating around about another possible attack.

That evening, public transportation started back up again, and Panteloglou began the trip home to Long Island, dropping students off at their homes along the way, or at least in the right direction.

“I took one kid home, Philip, and that was sad,” Panteloglou said. “His cousin worked on the 86th floor, so when I walked into the house it was like walking into a funeral. It was so sad.”

Eventually, Panteloglou reached his home in Valley Stream, NY at past two in the morning, where his family had been waiting with bated breath for news about him.

“[They] were freaked out, they had no idea where I was,” Panteloglou said. “My cell phone didn’t work, I had Verizon, the Verizon tower was in the tower, it went down…” Panteloglou trailed off, sighing.

“It was a day, that’s for sure.”

Against all odds

In the aftermath of the attacks on 9/11, the high school was shut down indefinitely. Students and faculty were moved to Norman Thomas High School on East 33rd St., and ended up staying there for six months. To make classes work with twice the number of people, the school day schedule for Echo was 12:30-5:30 p.m.

For a teacher like Panteloglou, the future of the school year seemed bleak.

“I really thought the year was awash, there was no way these kids were going to pass exams. How could they, after everything?” Panteloglou said. “But I’ve gotta be honest, I had more success academically that year than any other year.”

Panteloglou attributes this success to the close bond the students formed after the tragedy, students that he still keeps in touch with to this day.

“If it wasn’t for them, I don’t know how I would have dealt with it.”

But if the success of these students and the positive ways with which they handled the cards they were dealt touched Panteloglou and the rest of the staff, it’s clear not much attention was paid to them outside the walls of their temporary home at Norman Thomas.

“We were a block away”

About a mile away from where the towers once stood is Stuyvesant High School. While open to New York residents at no charge, prospective students are required to go through a competitive examination and selection process in order to get an acceptance. Ranked as a Gold Medal School in U.S. News & World Report, Stuyvesant High School is considered one of the most prestigious, public secondary schools in New York City.

Not surprisingly, the school and its students quickly became media darlings after 9/11, and because of its proximity to the World Trade Center, the students were dubbed “The Kids Who Saw it All.”

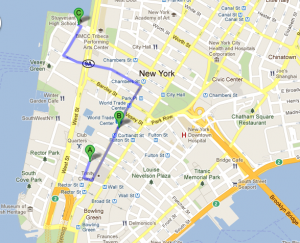

This map shows the proximity of Stuyvesant High School (Point C) and the High School of Economics and Finance (Point A) to the World Trade Center (Point B). MAP COURTESY OF GOOGLE

Like Echo, Stuyvesant students were also temporarily displaced, but the similarities stopped short there. They were sent to the equally renowned Brooklyn Technical High School for a little less than a month, while Echo students remained spent most of the school year at Norman Thomas, a school with a history of violence that is now considered a “Left Behind” school.

“Our school got no press whatsoever,” Panteloglou said. “It was always Stuyvesant this, Stuyvesant that. There were two schools closer to them.”

With memories of running from the clouds of smoke still fresh in their minds, the students of the High School of Economics and Finance couldn’t help but be upset and feel downright ignored.

“They were so angry,” Panteloglou said of his students. “They were angry at the media because it was always ‘Stuyvesant, the closest high school to Ground Zero.’ No, we were the closest, we were a block away. They felt like nobody cared about them, they really did.”

According to Panteloglou, the way the media and politicians reacted to Sept. 11 opened the eyes of the student body.

“Mayor Bloomberg was supposed to be our guest speaker at graduation that year, and the day before he cancelled for whatever reason,” Panteloglou said. “So not only did they not get any positive press, but…I mean I don’t want to say [the mayor] turned his back on 150 kids, but it definitely felt like it.”

Eventually, the school moved back into the building on Trinity Place, and administrators partnered with psychologists from St. Vincent’s Hospital to help students deal with the events of 9/11. A school in Texas also reached out and made donations to the school.

“It wasn’t all negative,” Panteloglou allows, “But sometimes it felt like people away from us cared more than those closest to us.”

Still, he doesn’t resent Stuyvesant for all of the press they got after Sept. 11. Everyone suffered, he says. It’s the media that didn’t do the research.

Coming to terms with 9/11

These days, Homer Panteloglou still grapples with what happened on September 11, 2001.

Upon returning to the high school in 2002, faculty and administrators were worried about whether there would be any health problems from Ground Zero. Fortunately, no one seems to have fallen ill from the asbestos that still hung in the air.

“I don’t feel like I’ve had any issues because of 9/11,” Panteloglou said. “Mental…that’s a different story.”

He still can’t watch the anniversary specials on television, especially after recognizing a friend in the footage of one program. In the few years after, he would get irritated whenever he saw tourists taking pictures of Ground Zero, essentially a graveyard of everyone who lost their lives that day.

Click here to listen to Homer Panteloglou’s thoughts on the 9/11 Memorial located at the World Trade Center site

“It’s been ten years,” Panteloglou said. “I’m good on 364 days of the year, but on that day, it always affects me. And I always say to myself ‘it gets a little better, it gets a little better,’ but…” He trails off. The memory is still there, on Panteloglou’s face as he recounts what happened on September 11. Even though time has passed and most wounds have healed, the memory is still there. It seems to be a different kind of better.